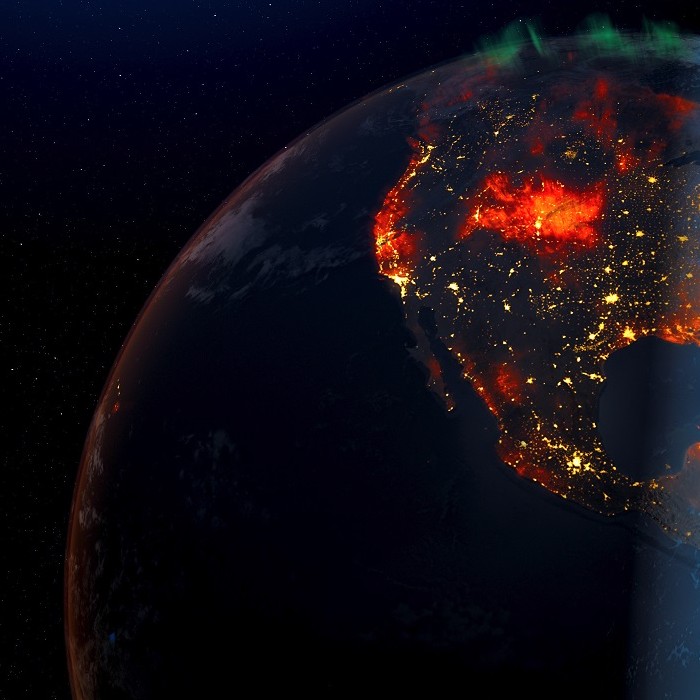

The Big One is coming. Scientists don’t know exactly when it will hit, and they don’t know exactly where. But sooner or later, they say, an earthquake of at least a 7.8 magnitude will occur along the southern part of California’s densely populated San Andreas Fault.

When that happens, it could cause more than 1,800 deaths, 50,000 injuries and $200 billion in damage, according to Forbes. It reported that a 7.8 quake would be at least 44 times stronger than the Northridge earthquake that hit Southern California in 1994. That earthquake caused 72 deaths, some 9,000 injuries and approximately $25 billion in damage.

The threat isn’t isolated to California, however. As it happens, earthquakes can happen almost anywhere. Earlier this year, New York City was surprised by its largest earthquake in 140 years, and that was a relatively small one.

During the last two decades, earthquakes have caused nearly 750,000 deaths worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, which says more than half of all deaths from natural disasters are from earthquakes.

Of course, it’s not just the quake itself that’s worrisome. When the ground suddenly starts shaking and shifting, fatal fires, tsunamis, landslides and avalanches can follow.

Unfortunately, neither earthquakes nor their aftermath can be prevented. Deaths from earthquakes, however, are another story, which is why organizations have spent years working on ways to provide immediate and lifesaving alerts. One of the latest tools is something more and more people have handy: a smartphone.

Using Smartphone Accelerometers for Earthquake Detection

In 2020, Google announced that it was building the world’s largest earthquake detection network. This warning system compiles data from Google’s vast web of Android phones to predict where earthquakes might strike. Its predictions could give just enough warning time to help people take shelter, and to slow trains or halt cars from entering sensitive infrastructure, potentially saving countless lives in the process.

At the heart of the system are sensors that can detect shaking, which already are embedded in most smartphones.

“Every smartphone has an accelerometer in it — the same type of sensor that the traditional seismic networks use to detect earthquakes,” said Richard Allen, director of the University of California Berkley’s Seismology Lab.

Because 2.5 billion mobile devices run the Android operating system worldwide, the Google earthquake alert system can reach rural areas in distant regions of the globe where typical detection systems are sparse or nonexistent. Phones are, therefore, proving to be yet another invaluable sensor in a world that’s being transformed and fueled by data.

Speed Saves – How Quick Earthquake Alerts Can Save Lives

When disaster is about to strike, every second matters. So, the wide-reaching impact of an Android earthquake alert could literally be lifesaving.

“We find that there are some earthquake warnings that could be faster by using phone triggers,” said Allen, who helped Google develop its crowdsourced approach for detecting earthquakes worldwide.

“We are seeing, on average, three times stronger shaking on the phone than we see on the traditional network.”

The reason for that is that phones are located where people are located.

“The earthquakes that the phones detect faster are out in very sparsely populated regions, which is where we have the fewest seismic stations,” Allen continued. “But the phones, of course, are exactly where people are, and so we can now see what it is that people are actually experiencing during the earthquake. It turns out that having just a few phones in those regions can make the warning seconds faster. That is really valuable.”

What makes warnings so valuable, of course, is what recipients can do with them.

“In recent earthquakes, we've seen that more than 50% of the injuries are because of people falling over or because of things falling onto people,” Allen said. “So we could actually reduce the number of injuries in an earthquake by 50% if everybody gets a warning and takes the action of dropping, covering and holding on.”

It's not just about what phones emit, which is warnings. It’s also about what they ingest, which is data.

“We can very gradually take apart the various sources of shake and help us better understand how earthquake ground motion interacts with the built environment in which we all live,” Allen said.

Regulators could use that kind of information to improve building codes, making collapse of roads, buildings and bridges less likely.

Enhancing Earthquake Alert Speed with Cloud Technology

While scientists are particularly interested in data from accelerometers, using smartphones for earthquake detection and response isn’t just theoretical or academic. It’s real and practical.

Take ShakeAlert, an app that provides early earthquake warnings across California, Oregon and Washington. Although it uses traditional seismic stations, ShakeAlert is also studying how phone sensors can eventually help it enhance its alerts.

“We can potentially provide a warning to people a few seconds to tens of seconds before they actually feel the shaking,” said Allen, who helped develop ShakeAlert.

“If the phone experiences shaking when it’s stationary, it goes into a monitoring mode. If it shakes, there’s an analysis to see if it looks like earthquake shaking. And if it does, it then records the ground motion and the seismic waveform just like traditional seismic networks do, and then it uploads that information.”

Google’s Android devices already utilize ShakeAlert regionally, and the private sector is using it to minimize damages and loss of life caused by sudden and violent shaking.

“The BART train system in the San Francisco Bay area automatically slows their trains whenever they get an alert to reduce the likelihood of a derailment,” Allen said. “There's a company that provides valve control systems for both fresh water and sewage, and they use it to reduce the likelihood of catastrophic failure. There's a bunch of other kinds of industrial applications, all aimed at reducing the losses resulting from an earthquake.”

The cloud is essential to handling data and alerts of this size and scale.

“The system is entirely in the cloud,” Allen said. “There's a whole backend that maintains and updates the app and generates and sends the alerts, and that’s all based in the cloud.”

Because ShakeAlert is a global app, servers are needed in different locations around the globe to support it.

“By having it all in the cloud, when there’s a lot of interest we can easily scale up,” Allen continued.

“For example, after an earthquake, a lot of people download the app. And when that happens, we can spin up additional servers to support all of those additional users very quickly.”

The cloud can also run AI-models that can predict earthquakes as The University of Texas recently tested. Their algorithm correctly predicted 70% of earthquakes a week before they even happened during a multi-month trial in China, marking a significant milestone in the future of earthquake forecasting.

Similarly, fiber optic undersea cables may also prove to be the next gold mine for earthquake data and detection.

The Expansive Potential of Mobile-Based Earthquake Detection

As the Android earthquake alerts system illustrates, smartphones may ultimately prove to be a game-changer in the future of earthquake detection.

“We are living in a world that has ever more sensors and ever more computational capability to understand what those sensors are telling us about,” Allen said. “I think there's a huge amount of potential that more data and observations will help to drive a better understanding of the actual ground shaking that we are all going to experience.”

In the San Francisco Bay Area alone there’s a two in three likelihood of a major damaging earthquake in the near future, according to Allen.

“I just hope that we can use this sensor data to better prepare for it,” he said.

Thanks to the sensors in their pockets, citizens’ phones could be the key to saving their own lives.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of the article that was originally published on October 19, 2023.

Chase Guttman is a technology writer. He’s also an award-winning travel photographer, Emmy-winning drone cinematographer, author, lecturer and instructor. His book, The Handbook of Drone Photography, was one of the first written on the topic and received critical acclaim. Find him at chaseguttman.com or @chaseguttman.

© 2023 Nutanix, Inc. All rights reserved. For additional legal information, please go here.